By Sheridan Wimmer on February 6, 2026

How Kansas farmers manage weather, safety and inputs

Between rain and roadways, Kansas farmers practice safety precautions during planting season.

To the east of the Mars chocolate plant south of Topeka, Ryan Johnson sets up for a long day of planting one of his fields to corn. It’s mid-April 2025 and it’s been dry, so Johnson checks the soil to see if he needs to change plans for the day. He attempts to plant but decides moisture will be necessary to give the crop the best chance of survival. While he would like to get this field planted, the life of a farmer means always being at the mercy of Mother Nature.

"Planting is the most important thing we do all year,” Johnson says. “If you get planting right, then you still have 100 percent of your potential in the field. Your best outcome is still possible and still in front of you."

The decision to wait for rain means he’ll need to adjust his expectations for the day (or possibly weeks) until it rains again on his non-irrigated acres. While most of us typically have set plans for certain days no matter what the forecast says, a farmer’s personality needs to be one prepared for adaptability, perseverance and mostly, a whole lot of hope.

The decision to wait for rain means he’ll need to adjust his expectations for the day (or possibly weeks) until it rains again on his non-irrigated acres. While most of us typically have set plans for certain days no matter what the forecast says, a farmer’s personality needs to be one prepared for adaptability, perseverance and mostly, a whole lot of hope.

While Johnson couldn’t plant that day, he isn’t one to sit idle when Mother Nature doesn’t cooperate. His best remedy for our uncooperative weather in Kansas is to do things in his “spare” time that he will thank himself for later.

“I make sure everything I need to do is ready before things need to happen,” he says. “The better job I can do at being prepared, the better it allows me to use the windows of time that I have more effectively. It pays dividends to be proactive in using those delays to do the work I will need done in the future.”

Mother Nature is fickle, and when farmers want more or less moisture, they know to be careful about what they ask or pray for. On that day in April when it was too dry to plant, Mother Nature was listening, and it rained so much Johnson had to wait three weeks to plant.

“It rained that night, and then before we ever could get back in the field, it rained again,” he says. “Then it rained some more. And it was about the 10th or 11th of May when I got the last two days of planting done.”

Planting any crop late can impact its yield.

“If you have corn planted April 10 versus May 10 versus June 10, your yield expectations are wildly different as you go down the calendar,” Johnson says. “When we have weather events like the one we had last April that prevent us from getting work done, it can be very stressful.”

Share the road

That kind of pressure to get things planted when they need to be can mean long days in the tractor. Johnson says he doesn’t work in the tractor more than 14 hours in a day, which he admits can be arduous, but safety is at the forefront of his mind — whether it’s the amount of sleep he gets, working with hazardous chemicals or staying aware of other people on the roadways, Johnson’s precautions are the most important thing he controls.

“Between the time I spend in the morning getting everything ready and the time I spend in the evening when I’m done, 14 hours is my limit,” Johnson says. “Long days are draining when they are happening one after another, which can happen during planting and harvest seasons, so it’s important to get a lot of rest. As a farmer, I have to stay on my toes when I’m in the field and taking things down the road."

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting had the highest rate of fatal work injuries of any sector in 2022. Tractor rollovers, equipment entanglements and roadway crashes are among the common causes.

Rest and roadway safety go together — whether you’re hauling a 40-foot John Deere planter with a tractor or you’re driving a Toyota Camry. For farmers, additional weight and increased width require extra precautions — not only from the farmer driving but also from other drivers on the roads.

“The average person may not completely understand how a tractor or a fully loaded semi behaves,” Johnson says. “We as farmers always have to be cognizant of other drivers around us. Situational awareness is a very important part of using large equipment.”

Because his farm is near Topeka, Johnson and other farmers near urban areas have to be mindful of the time when moving equipment or working in the fields.

“If I’m moving a combine during the 5 p.m. rush hour and everybody is heading home from work, I do my best to go slow and be patient, and really, that’s all I can ask from the people around me, too” Johnson says. “Just be mindful that we can’t always see you — and the best thing other drivers can do is obey traffic laws, especially passing zones. If I’m driving down the road and you can’t see around me, don’t go around me.”

Even crops take their turn

Johnson’s mindset of awareness and responsibility carries over into his farming practices. Just like safety precautions, managing his fields also takes precision and thoughtful considerations. From utilizing crop rotation practices to manage weeds and pests to the judicious use of inputs like pesticides, Johnson takes each decision seriously.

Row crop fields like corn, soybeans, wheat and milo typically aren’t planted to the same crop each year. Farmers may plant soybeans in a particular field one year, then the next they’ll plant corn in the same field. This practice, called crop rotation, is used to protect the soil from experiencing the same pressures year after year — a bit like rotating the tires on that Toyota Camry.

“Crop-specific diseases and pests can get worse very quickly if the crop is not rotated from one to another,” Johnson says. “Corn is a grass crop; soybeans are a legume. With different types of crops comes different types of weed and disease pressures. You want to be able to use different types of control measures in different years to keep weeds and diseases at bay.”

To help garner healthier soils, Johnson says corn has a great ability to add organic matter to the soil since the plant has a large root structure and helps hold soil in place better throughout the winter than other, smaller crops like soybeans. But soybeans help fix nitrogen in the soil, also making it an important element to caring for soil.

Protecting the food supply

When it comes to inputs, farmers do their due diligence in deciding what works best for their soil, fields, crops and finances. Johnson says he uses two main types of herbicides — residual, which prevent weed germination and kills seedlings before they emerge, and herbicides that clear established weeds from a field.

“We will usually use two applications of residual herbicides — one as a pre-plant or immediately after planting our crop, then another one partway through the growing season to add more length to the coverage and prevent new weeds from coming up,” Johnson says. “For the other type of herbicide, we have to take budget into consideration. This year, I used split applications at higher total rates, and it worked really well and cost me less money. You could spend a king’s ransom on herbicides, but if the weather cooperates, you can reduce your herbicide expenses.”

Pesticides for farmers has always been and will always be an important tool in their toolbox. And that means using them responsibly.

“Nobody is interested in using more pesticides than they need to,” Johnson says. “And they’re not interested in using them at the risk of consumer or animal health. We eat the same food as everybody else. I’m not doing anything on my farm that would endanger anyone’s food supply because that would mean endangering my own food supply. It just doesn’t make sense to do that.”

The use of pesticides is also heavily regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency under federal laws like the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act and the Food Quality Protection Act. The products are clearly labeled for certain uses and certain conditions and include deadlines for application to ensure residues are not present in the crop when it goes to harvest.

Johnson, like many farmers, has an applicator’s license, which is required to buy and use certain pesticides.

“I’ve spent most of the time I’ve been farming researching inputs like herbicides and pesticides,” Johnson says. “I want to know how they work and how well they work and when they are best used. I’ve found a balance between cost and effectiveness while still being safe and staying within the lawful bounds of the products.”

That time he’s spent looking into inputs like herbicides and pesticides isn’t uncommon. Farmers across the state and our country tirelessly work to protect their land and the crops they raise to enhance our food supply — because at the end of the day, it’s their food supply, too.

Powering our food and fuel needs

Corn is one of Kansas’ top commodities, supporting the state’s economy with billions in economic output — but even more important are the people planting, growing, caring for and harvesting the product many industries depend on. From livestock feed to ethanol, field corn is an integral asset to our food and fuel needs. During planting season this spring, watch out for our farmers like Johnson, especially on our state’s highways. They’ve likely put in multiple 14-hour days and want to go home to their families.

---

Safe driving tips during Kansas’ planting season

Slow down and be courteous to farm equipment and machinery on roadways. A few tips to driving safely during planting season, or anytime farm equipment is on the roadways:

- Decelerate early – As soon as you see farm machinery, reduce your speed. You are coming up on a slow-moving vehicle faster than you think.

- Keep your distance – A distance of about 50 feet away from the machinery in front of you is a good rule of thumb.

- Watch for wide turns and don’t assume which way it’s turning – Tractors may be turning left, but need to pull to the right to prepare for the wide turn.

- Look for slow-moving vehicle (SMV emblems) – This is a reflective, red-and-orange triangle on the back of farm equipment. It is required for farmers to utilize on machinery that operates at speeds of less than 25 miles per hour on public highways.

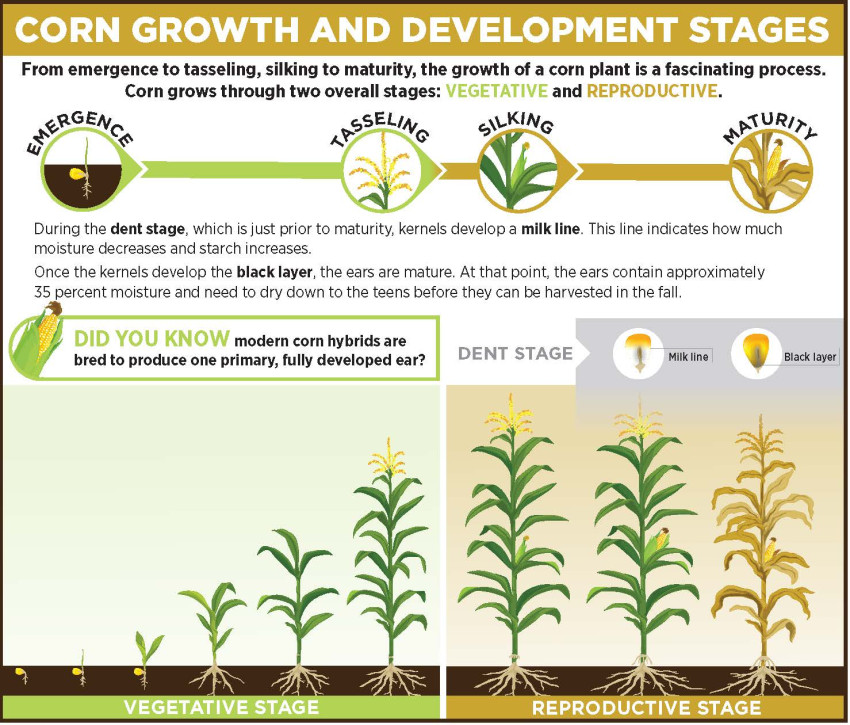

Corn growth and development stages

Did you know each corn plant develops just one ear of corn? That’s why farmers carefully manage spacing, nutrients and care so they can reach their full potential.

The corn growth and development process is in depth. Within the two overall development stages – vegetative and reproductive – are steps to its growth. From emergence to tasseling, silking to maturity, the growth of a corn plant is a fascinating process. During the dent stage, which is just prior to maturity, kernels develop what is called a “milk line.” This line indicates how much moisture decreases and starch increases. The kernels look like your favorite fall candy — candy corn. You love it or you hate it. There’s no in between. Once the kernel develops what is called the “black layer,” that’s when the ears are mature. At that point, the ears contain approximately 35 percent moisture and need to dry down to the teens before they can be harvested in the fall.