By Brandi Buzzard on November 17, 2020

Breeding Season: Tinder For Cows

Almost as soon as calving season is over, we start working on our game plan for the next set of calves by preparing our cows for breeding. The gestation length of a cow is 283 days, so even though September 2021 seems extremely far away, we are making breeding plans for our cows in the weeks leading up to Thanksgiving.

A critical step in planning the upcoming matings for our cow herd is evaluating the current year’s calving records to examine what worked and what didn’t from breeding plans in 2019. For example, if cow #A007 has a great-looking calf at her side, we will likely try to replicate that mating to get another calf of similar quality. We will also evaluate our yearling bull and heifer calves to see which of those matings worked out well and duplicate them, if possible. As the old saying goes, “If it’s not broken, don’t fix it.”

When it comes to the actual breeding, we have three main methods – artificial insemination, embryo transfer and natural breeding. To artificially inseminate a cow, or transfer and implant an embryo, we follow a timed breeding protocol using naturally occurring hormones, as well as heat indicators, to breed the cows at the optimum phase of their estrous cycle. These reproductive methods require a significant amount of planning and logistical coordination to ensure our vet is available for breeding, the cows are in heat and the resulting calf is born in our preferred calving window the following fall.

We also like to use as many commercial cows (which are not purebred or registered) as possible as recipients for embryos from our purebred cows. These commercial cows have proven themselves to possess all the qualities of a wonderful mama – great milking ability, docile and easy calving, to name a few – and earned a spot as a recipient cow. They will be a surrogate for an embryo from one of our purebred cows since we strive to get as many purebred calves as possible every year so we have more bulls to sell.

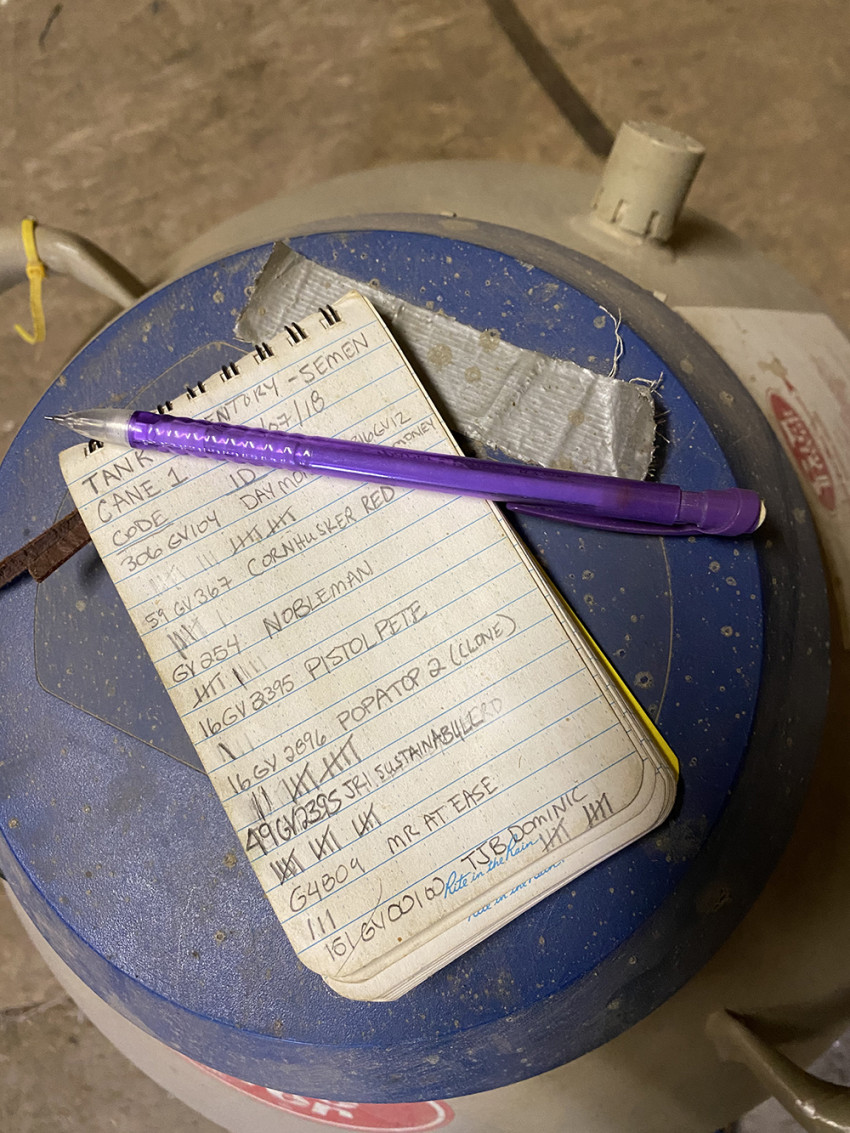

Sometimes we are unable to replicate certain matings if we don’t have semen from the preferred bull. While we do use natural service sires, we also order bull semen from other cattle farmers and ranchers to utilize their genetics to help us reach our production goals. We store the semen, which comes in small straws, in a big tank filled with liquid nitrogen to keep it preserved. We keep an accurate inventory on the contents of the tank and consult the records before breeding. If necessary, we’ll reorder certain semen that yielded great results or we will find a replacement for semen that is no longer available (from a bull that has died, for example).

Conversely, natural service sires or “herd bulls” are bulls that are turned out with the cows for approximately 60 days and have one job: to breed any cow that comes into heat. We generally purchase our herd bulls from other cattle farmers or ranchers based on their genetic capability and physical structure. The bulls then live on our ranch and we use them for up to five seasons to breed any cows that don’t conceive from artificial insemination or embryo transfer. We choose certain bulls based on what group of cows they will breed – for example, we will choose a herd bull that has lower birthweight genetics for use on our heifers, which have never given birth before, in order to avoid any potential calving difficulties. These bulls have a cushy life – open pastures and meal delivery 24/7/365 for a mere two months of work.

Cattle breeding has come a long way over the past several decades – what once was a game of chance has become a finely tuned process, designed to yield the best possible results using science, art and even a little bit of luck.