By Rick McNary on July 25, 2017

All in the family

This farm family loves rodeos and a special kind of cowboy art

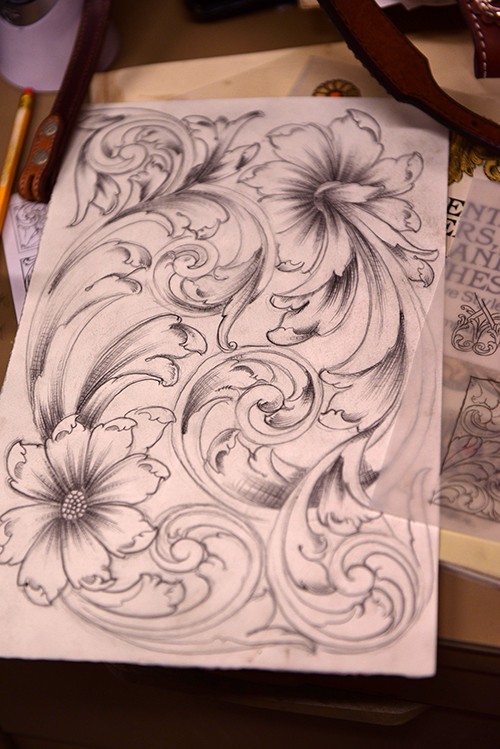

Troy Flaharty has a different morning routine than most cowboys--he spends his first 30 minutes drawing. He is perfecting a technique to create traditional cowboy art in the form of bits and spurs.

Troy Flaharty has a different morning routine than most cowboys--he spends his first 30 minutes drawing. He is perfecting a technique to create traditional cowboy art in the form of bits and spurs.

“I grew up around horses,” Troy says. “I’ve always been interested in making bits and spurs and dabbled in it as a hobby for a long time. Then a few years ago a friend said, ‘you will never sell a $5,000 bit until you make a $5,000 bit.’ It’s like anything; you can be a Wal-Mart or you can be a Neiman Marcus; I want to be a Neiman Marcus.”

Troy recently won a fellowship awarded by the Traditional Cowboy Arts Association (TCAA) which is dedicated to preserving and promoting the skills of saddlemaking, bit and spur making, silversmithing and rawhide braiding and the role of these traditional crafts in the cowboy culture of the North American West.

“The TCAA Fellowship is awarded once a year to two different people to help them study under the masters. I was awarded it this year and I’ve already studied two different times under one master bit and spur maker in Texas, then I’ll go out to Wyoming this fall for another. They are great teachers, but harsh critics. They expect the exceptional and won’t ease up until you create excellence.”

Troy creates most of his items using Chromalloy, the same metal used to build racecars. Some of his carving is done the old-fashioned way using a hammer and chisel, while he carves others under a microscope using an air-powered device much like a micro-jackhammer.

Troy creates most of his items using Chromalloy, the same metal used to build racecars. Some of his carving is done the old-fashioned way using a hammer and chisel, while he carves others under a microscope using an air-powered device much like a micro-jackhammer.

“Sometimes when I’m carving under a microscope, I think it looks horrible,” Troy jokes. “But then I pull it out and look at it with the naked eye and it looks fantastic. But the problem is I know what it looks like under the scope so I’m not satisfied until it’s perfect.”

Although some refer to him as a silversmith, Troy labels himself as a bit and spur maker.

"Silversmiths work mostly with silver and gold,” Troy says. “I use it some in my work, but most of what I use is high-carbon metal, which is stronger for the types of things I make.”

Family tradition

Troy, along with his wife, Colette, and daughter, Rio, live near El Dorado. Colette grew up on a ranch in the Flint Hills and first met Troy at a rodeo where he was bulldogging and calf-roping.

Troy, along with his wife, Colette, and daughter, Rio, live near El Dorado. Colette grew up on a ranch in the Flint Hills and first met Troy at a rodeo where he was bulldogging and calf-roping.

“I started riding horses about the same time I learned to walk,” Colette says. “As I grew older, I wanted to do barrel racing in rodeos. Winning at barrel racing depends on the quality of a horse and how well it’s trained.”

“There’s a reason I’m not a pro-basketball player,” Troy jokes. “I could get the best training in the world, but I don’t have what it takes. Horses are the same way; you have to have the right horse.”

“The best horse I ever had was a Quarter Horse named Catfish,” Colette says. “These horses are like Olympic athletes and they run hard. Running barrels seems to be easy and simple until you start going 30 miles per hour.”

She goes on to explain the sport is hard on a horse because of the way they stop quickly, turn and accelerate again. The family saw this first hand with Catfish who was injured and had to quit racing.

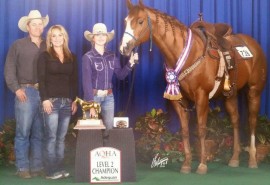

A few years back, Troy and Colette were able to purchase the full brother of Catfish from a breeder in Alabama. They named him The Wonder Bug and, after Troy and Colette trained him, she began to win various national competitions with him. Then Rio, their 11-year-old daughter, decided to start barrel racing.

A few years back, Troy and Colette were able to purchase the full brother of Catfish from a breeder in Alabama. They named him The Wonder Bug and, after Troy and Colette trained him, she began to win various national competitions with him. Then Rio, their 11-year-old daughter, decided to start barrel racing.

“We named her Rio Belle for two reasons,” Troy says. “One was because we lived near the Rio Grande when she was born and the second was because I could fit her whole name on a spur.”

Since she started barrel racing, Rio, now 14, has won an amazing collection of trophy saddles, belt buckles and even a horse trailer. Along the way, Colette and Troy gave the horse to Rio.

“His name is The Wonder Bug, but I just call him Brother since he was Catfish’s brother,” Rio says. “I just love him.”

The Flahartys treat The Wonder Bug as if he is a highly trained Olympic athlete. His diet, exercise and even swimming regimens are designed to ensure peak performance and minimize the risk of injury.

“There is no question that The Wonder Bug is Rio’s horse,” Colette says. “Troy and I will try to put a blanket on him in the winter and he hides in the corner. Rio can go out there dragging it along flapping in the wind and he almost kneels down to have her put it on him.”

Rio has been riding in various competitions across the U.S., but the one preparing her for her ultimate goal to ride in the National Finals Rodeo is the National Junior High and National High School Rodeo associations.

Rio has been riding in various competitions across the U.S., but the one preparing her for her ultimate goal to ride in the National Finals Rodeo is the National Junior High and National High School Rodeo associations.

“The Junior High and High School Rodeo Associations are structured like the pros by the way they keep track of points and earnings,” Colette says. “Rio will be able to ride professionally when she turns 18.”

“Dad and Mom have been so good to me but the best thing they’ve taught me is to be humble, nice and to ride quiet,” Rio says.

The Flahartys recently moved back to Kansas to be near family, friends and the land they love. They are a reminder of ingenious farmers and ranchers who fashion unique ways to make a living. The Flahartys choose do to it as artists and athletes.

And, like any farmer or rancher you’ll meet, they all choose to ride quiet.