By Greg Doering on February 7, 2020

Farming Legacies

Keeping farms in the family for more than 150 years

Wilhelm Berges would have walked more than 20 miles from Seneca to arrive at the 160-acre parcel of land he bought in 1868 from his half-brother and the Kansas Pacific Railroad Company.

The German-born Berges was one of the one million-plus people who streamed into Kansas after the Civil War. Berges, who arrived at a nearly treeless prairie, built his house, which eventually housed a family of 13, and outbuildings out of limestone blocks. The nearest town to the east was Holton and Manhattan was 26 miles southwest as the crow flies. His wife, Wilhelmina, gave birth to 10 of their children in Pottawatomie County. They were pioneers underpinning a newly minted state, and they were also laying a family foundation for generations.

Today, the Berges’ limestone house, built in 1875, still stands, and Wilhelm’s great-great-grandson Jonathan Berges is managing the farm.

The Berges family outside their Sesquicentennial Farm.

The operation has grown from the original quarter section to just under 5,000 acres. (An acre is about the size of a football field.) The nearest town is Onaga, about five miles away. And you can hear vehicles going down Kansas Highway 16 from inside the original house.

A view of limestone-block home built in 1875 by Wilhelm Berges in northern Pottawatomie County.

150 YEARS OF FARMING

The Bergeses are one of 29 families to receive Kansas Farm Bureau’s Sesquicentennial Farm designation in its inaugural year. To be eligible, an applicant must be a Farm Bureau member in Kansas, have owned a tract of at least 80 acres continuously for 150 years or more, and the current owner must be related to the original owner.

While settlement in Kansas was first opened in 1854, it wasn’t until nearly a decade later that the Homestead Act made free or cheap land available and attractive to many settlers. More than 70 percent of the immigrants arriving in Kansas were engaged in agriculture, which remained the principal occupation for residents until the 1920s, according to the Kansas Historical Society. Wilhelm bought his initial quarter section — the equivalent of one-fourth of a square mile — for $3.25 an acre.

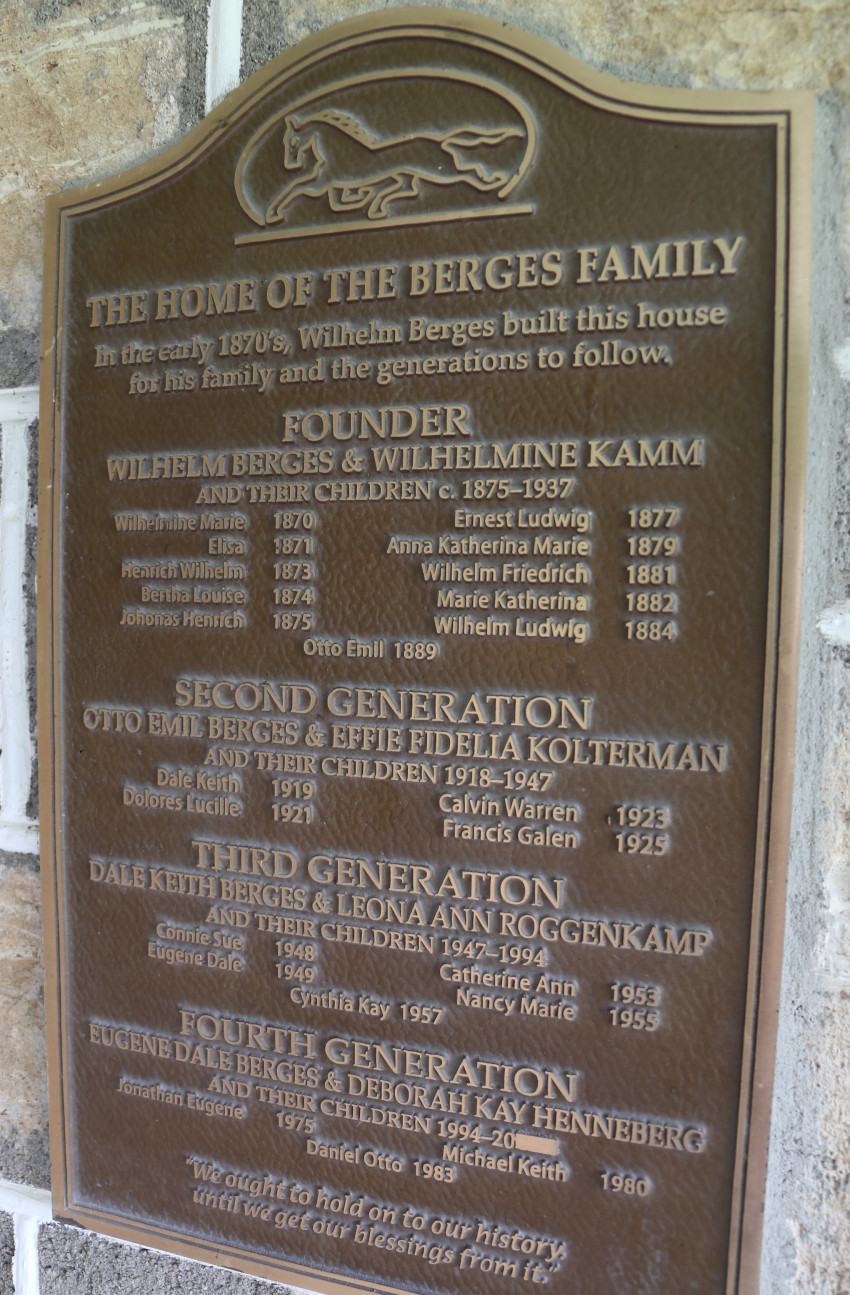

A bronze plaque lists the four generations of Bergeses who have lived in the original limestone home near Onaga.

HOME ON THE RANGE

Thomas Koeneke and his wife, Maria Schotte Koeneke, homesteaded a tract of land south of the Nebraska border in Marshall County. The Koeneke family was traveling to California with their sister-in-law, Maria Kulenkamp Schotte, and her family, when one of the wagons broke down just past a creek with a horseshoe bend.

To survive the first winter, the Koenekes and Schottes dug a dwelling into the side of a hill that offered a sweeping view of the creek valley below.

“You can still see where they kind of went into the hill," Scott Schotte says.

The Koenekes settled on the west side of the horseshoe bend and the Schottes staked out a claim to the east. Both tracts are under the Schotte name today, and both are Kansas Farm Bureau Sesquicentennial Farms belonging to the Koenekes’ great-great nephew Scott Schotte and his wife, Jami, on the west side of the bend in Horseshoe Creek. Delmar Schotte owns the land first settled by Johann and Maria Schotte.

The land was claimed for “free” under the Homestead Act, which was a three-step process: File an application, improve the land and file for the deed or patent. Nearly 90,000 homesteaders claimed more than 13 million acres of Kansas through the process. That’s about 25 percent of the 52 million-plus acres in the state. Across the nation, the program distributed 270 million acres, or about 10 percent of the landmass of the United States.

The original two-story home built by Thomas Koeneke in Marshall County, about three miles from the Nebraska border.

SUCCESSION PLANNING

It takes hard work and a little luck to keep the same ground in a family for 150-plus years. Land can be divided among heirs or sold with the cash distributed among the surviving family. Both the Berges and Schotte clans have

had good fortune in keeping their land in the family.

“It’s always kind of a struggle,” Eugene Berges says of working out a transition plan. “My sisters were very generous and kept the farm together. I think my sons would be able to maintain it that way, too.”

Jonathan Berges eased into managing the operation, first taking over the corn before moving into overseeing all the crops. Next he took on the cattle. A few years ago, Eugene says, Jonathan also took over all the recordkeeping and taxes.

“I kind of work for him now,” Eugene says. “It’s not too bad. I don’t have to do the worrying or planning. I just show up, and he does everything else.”

The Koeneke farm could have slipped out of the family when its third-generation owner, Alfred Koeneke, Thomas’ grandson, died. His daughters sold the ground at public auction, but great nephews Donald and Richard Schotte bought it. Scott purchased the ground from his dad and uncle in 2000. He now grows corn, soybeans and alfalfa, and raises cattle on the land.

The Schotte family, who now grows corn, soybeans and alfalfa, and raises cattle on their Sesquicentennial Farm.

ORIGINAL STRUCTURES

In addition to the house, the Berges farm also boasts a shed and horse barn built in the 1880s. Like the house, they were built with limestone blocks quarried by hammering pins and feathers into the rock until it cleaved.

A view of the Berges Farm horse barn built in 1881.

On Delmar Schotte’s farm, there’s a 40-by-80-foot barn built by Johann Schotte, but it’s not in its original location. After the creek repeatedly flooded, the wooden barn was moved a quarter mile away to higher ground with a stump puller. The barn was lifted and set on rollers, then the stump puller — which was actually a horsedrawn turnstile that wound a cable on a drum — pulled the structure inch-by-inch to higher ground. It took four men and a horse to move the barn to its new stone foundation.

A 40-by-80-foot barn built by Johann Schotte sits on Delmar Schotte’s farm today. The barn was moved about a quarter mile uphill after repeated floods along Horseshoe Creek.

REAPING THE REWARDS

“We’re proud of 150 years, but we had a lot of help,” Eugene Berges says of the milestone.

He recalls one spring when his neighbors helped get the cattle to grass because he’d broken his leg. Eugene also credits new technology and researchers at Kansas State University for helping transform the farm from a general operation into a successful business, despite pitfalls like bad weather, low prices and changes in consumer preferences.

Why keep doing it then?

“That’s a tough question,” Jonathan Berges says, before settling on the satisfaction of selling a load of calves and seeing the enjoyment his three children get from living in the countryside.

Scott Schotte’s oldest son is on the path to become the sixth generation to work the land. Scott says his son forgoes extracurricular activities at school because he doesn’t want to miss anything on the farm.

For Eugene, though, the most satisfying part of the job has been watching Jonathan take over and improve the operation.

“He’s better at farming than I am,” Eugene says. “That’s been a reward.”

Twenty-nine families were awarded the Sesquicentennial Farm Award in 2019 through Kansas Farm Bureau, showcasing the state’s rich history in agriculture and farm-family resilience.

Learn more about the Century and Sesquicentennial Farms Program at www.kfb.org/centuryfarm.