By Rick McNary on February 24, 2017

Neighbor helping neighbor

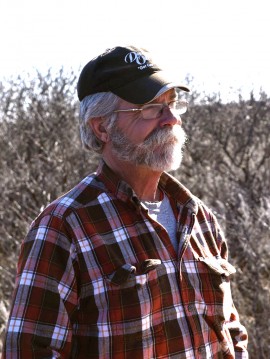

Dennis Ricke scans the Gyp Hills near Medicine Lodge for smoke each day like he has for more than three decades. As a farmer and a volunteer firefighter, even the sight of smoke 18 miles away causes alarm.

“I joined the rural fire department when I moved back to the family farm 30 years ago to help us and our neighbors protect our places,” Dennis says. “Fires out here are living, breathing monsters that have a mind of their own. When the wind blows 50 miles an hour, the fire sounds like a freight train and the cedar trees explode like ten-gallon gas cans. It can rattle a feller.”

Dennis, farmer, cowboy and president of the Barber County Farm Bureau, is also the Union Chapel Fire Station manager. Volunteer firefighters are paid $15 per run, whether it lasts for an afternoon or a week.

“We do it for the money,” Dennis jokes.

“Fighting fires gets in your blood. When you’re out on a fire call, it’s pure adrenaline. I usually don’t get scared except that time back in ’96 when I was trapped in a ravine with fire on both sides and over the top. We had to use the water in the truck to spray ourselves down. That made me a little nervous.”

In early 2016, Dennis spent nearly a month helping fight the Anderson Creek Fire that scorched more than 400,000 acres and destroyed homes, livestock, crops and property. Miraculously, no human lives were lost.

“Even from 18 miles away, we could tell it was a monster,” Dennis says. “We’d try to head it in one direction, but it would laugh at us and head another way.”

It was common to have 50 to 60 trucks from various volunteer fire departments in Kansas and Oklahoma scattered across the fire.

“In rural areas like ours, everyone helps in some way,” Dennis says. “Some see our trucks and bring us food and water. After several days of fighting fire, there’s nothing as delicious as a baloney-and-cheese sandwich.”

Over time, various donations poured into the area from all over the U.S.

“Everyone wanted to help. When our folks went to the grocery store in town to pick up food for the firefighters, the store didn’t charge them.”

Many of the rural fire departments are staffed with volunteers who are also farmers.

“We live here and know every back road, short cut, deep ravine and dangerous road. For example, we know when we fight fire on the ranch with the buffalo not to run our sirens because they think a feed truck is calling them in. It’s nearly impossible to move a buffalo out of the way.”

While some of the farmers serve as volunteer firefighters, others assist in helpful ways.

“Some farmers take a tractor over to the neighbors and disc up the pasture around their home. Others create protection around neighbor’s homes using their bulldozers.”

During the Anderson Creek Fire, farmers cut fences along their own fields to let the neighbor’s cattle on their green wheat to save them from the fire.

“The hardest part of this job is telling people they have to evacuate their homes. Usually someone above me in the chain of command makes that call, but I’m the messenger. People don’t want to leave their homes even though their lives are in danger.”

Many of the farmers and ranchers who were helping others fight the fire lost much of their own property and cattle.

“The saddest part was some of the neighbors couldn’t save their stock. The fire burned the hair off the animals, but they were still alive. Guys had a real hard time killing their own cows and calves, but they had to put them out of their pain.”

Some of the most extensive damage to property was the destruction of thousands of miles of fencing that used hedge limbs from the prolific Osage Orange trees as fence posts.

“At night, those burning hedge posts looked like airport runway lights. The cottonwood trees on fire looked like Christmas lights and the milo stubble burned like roman candles. It was pretty, but it was devastating.”

As one drives through the area now, gleaming new barbed wire and metal fence posts give evidence of where the fire burned. Unscathed areas still have fence strung on hedge posts.

“The fire was so hot, it even burned the asphalt in various spots on the highway.”

“We had spring rains that helped somewhat, then a bad ice storm in winter that downed power lines and busted up trees. Whoever upset Mother Nature ought to try making up with her again.”

Along the drive on the back roads, Dennis points out a pickup with a horse trailer perched on a ridge overlooking the valley.

“That belonged to ol’ Pete who loved to hunt coyotes from horseback with his dogs. When Pete died, the neighbors bought the truck and trailer off his widow and perched it on that hill so ol’ Pete can watch over us. The fire left Pete’s truck alone.”

Dennis is like countless farmers who give of their time, resources and skills to help their community. They serve on school boards, church committees, county commissions, parent/teacher organizations and a host of other positions. In 2016, Kansas Farm Bureau members accumulated 116,000 hours of volunteering.

Farmers are like good Samaritans that consider anyone in need, including strangers and even enemies, as their neighbor. When other farmers in their community are sick, they fire up their combines to harvest crops and throw pancake feeds and barbecues to raise funds. They understand better than most that community is based on needing each other both to survive and thrive.

When asked how many cattle Dennis has, he answered in the context of community.

“Well, I only own about 150, but if you consider all of us neighbors looking out for each other’s cattle, I’d say about 1,000.”

Looking out for each other. That’s what farmers do better than most.

Just ask ol’ Pete.